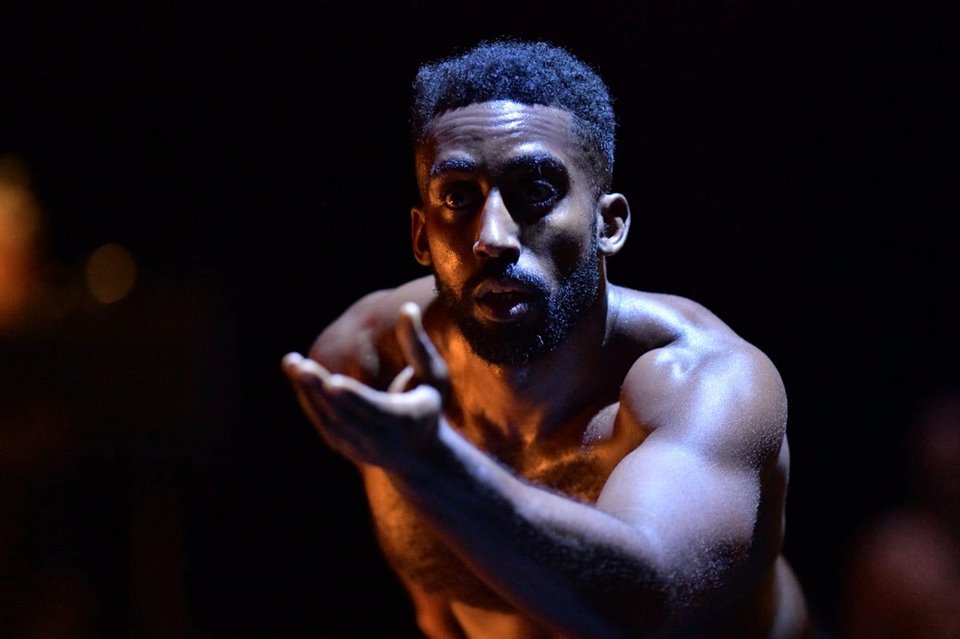

Bolewa Sabourin, a French dancer of Congolese origin, co-founder of the Loba association, has made dance a therapy for him, because of his colourful career, but above all for others, especially for women whose bodies were bruised by violence and a source of reflection on the male gender at the beginning of the 21stcentury.

Summarizing Bolewa Sabourin’s life is a challenge worthy of the person. Born in 1985 in Paris to a Congolese father from Mbandaka (Democratic Republic of Congo) and a French mother from La Rochelle, Bolewa was taken by his father to Kinshasa at the age of one to be with his grandparents when he was torn away from his mother. Until he was six years old, he lived in a poor neighbourhood of the capital of the former Zaire with his grandparents, until his father made him return to Paris or Saint-Denis, moving from house to house over the years and according to his father’s encounters, as he indicates in his autobiographyLa rage de vivre. Not enough to have a certain stability. But that made the future dancer resourceful and “hypersensitive”. Balla Fofana, co-author of Bolewa’s autobiography, confirms this great sensitivity in the latter. “I’ve almost always lived outside. You are immediately confronted with raw reality. I always had to answer, otherwise I would always be crushed,” confesses Bolewa. He was reunited with his mother at the age of 11 and left for Martinique a year later, where he met three half-brothers. But he left for Paris a year later, due to a difficult mother-son relationship or an outside view of him as a “negro”, giving him the impression of being “everywhere and nowhere at the same time”

Dance, a personal therapy…

At the age of nine, Bolewa was introduced to dance by a friend of his father’s, a dancer. A figure who had a great influence on the thirty-year-old. “I danced with him and that was my lifeline. I felt all this freedom that I didn’t have elsewhere in the world I was living in, it lifted me up, allowed me to express a lot of things that I couldn’t express outside” analyses Bolewa, grateful to his mentor and anxious to use it as an instrument of therapy, which he used for himself, especially after failing his bachelor’s degree in electro-technical STI. When he wasn’t doing well, even when we went out in the evenings, when he had his dance classes, it was a breath of fresh air that allowed him to completely disconnect from reality, daily life, etc. “When he wasn’t doing well, even when we went out in the evenings, when he had his dance classes, it was a breath of fresh air that allowed him to completely disconnect from reality, daily life, etc.”. I think he is the first one to have tested his therapy,” says Bruno Contencin, a friend of Bolewa’s since his return from Martinique, at the time of the college, witnessing his friend’s years of trouble and his success with his association Loba, meaning “express yourself” in Lingala, one of the four national languages of the DRC.

Co-founder, with Bolewa, of the Loba association, William Njaboum shares Bolewa’s vision of art as a tool “at the service of the city”. “Art is a moment of truth. It’s a moment where you can’t hide. And to use art to serve the city is to propose to the world what we are. We think that it is by the singularity of each other that we manage to build a world a little truer, a little more coherent, a world where we manage to get rid of certain shackles, of certain preconceived ideas” he says. For Balla, this vision of art, developed by Bolewa and William, allows one to surpass oneself and to build a community that cares for others. “His commitment allows us to return to the primary missions of art before the spectacle and commodification,” he analyses.

At the same time, even though he did not have the baccalaureate, Bolewa graduated with a Master’s degree in Concertation Engineering in Political Science from the University of Paris 1 in 2015. “It’s to show the aberration of this system, which does not build individuals, which does not educate individuals so that they can think for themselves, but so that they can spit out the knowledge that is stuffed into their heads. To condition them rather than to make them truly free thinkers who have their true free will” Bolewa tackles. “He forces admiration for his ability to free himself from a determinism that we can sometimes dwell on,” stresses William.

… and collective

This experimentation with dance as individual therapy being assured, Bolewa and William seek to deploy it for the collective, from different angles. “Each time, we decline. Putting art at the service of the city. Then put art at the service of health. Then, on a more personal scale, and that’s what we do in high schools, we put art at the service of education. And especially about violence against women. “Using dance to help traumatized women is just a huge thing and these are really magical moments, having attended the workshops,” says Flora Delhove, a dancer working alongside Bolewa in the association. What pushed Bolewa to be attentive to the plight of women was her meeting with Congolese doctor Denis Mukwege in Paris on 8 March 2016. This was a revealing moment for the dancer, keen to help women victims of rape as a weapon of war in Eastern Congo. “When I asked the doctor how I could help him, he asked me to do a project. I proposed a project around dance as a tool for psychological reconstruction,” he says. A year later, going to Bukavu, the city where Dr. Mukwege works, Bolewa developed his project on the spot and came away marked by his stay. “Instead of just making the women dance, we would make them dance and talk. I would have them dance, in parallel with a psychologist, a psychiatrist, who would make them talk right after my dancing time and we would combine the two, together. Not one after the other. […] How we use dance to allow them to cure themselves psychologically. So, what techniques are going to be used to go and touch the brain during dance workshops? …] Going there slapped me in the face. To see the resilience of women. You realize that everything you’ve been through, you’re privileged, you look like shit. You’re off-center. And that’s where it’s been great. …it showed that what I was doing had a purpose. It made them feel good. It made them feel better. That’s a hell of a grace, a hell of a reward. It’s useful for me and for others. That’s the way I go. That’s where I have to go,” he recalls, moved by the experience. “One of the big goals of the association, and of Bolewa in particular, is to go back to the women so that we can do more,” adds Flora, who became friends with Bolewa on her return from DRC.

Reflection on masculinity in the 21stcentury

This stay left such a lasting impression on Bolewa that he and his sidekick William embarked on a general reflection on masculinity in the 21st century, organized around workshops, dance performances and conferences. “It was this workshop that triggered the project,” says William, measuring the influence of his stay in Bukavu with women victims of rape as a weapon of war in Bolewa’s reflection on masculinity. But for Bolewa, the most important thing “is not that it gives answers, but that it raises questions. And among these questions is “what does it mean to be a man? It’s a whole programme in relation to one’s identity. Bolewa, for its part, claims a plural identity. “She is Congolese and French. She’s bourgeois, bobo, and rocks from the working class neighborhoods”. For William, this debate is an opportunity for men to refocus on themselves, on who they are. “They’re building a chimera Superman, which everybody wants to be, and they realize that this Superman, by definition, doesn’t exist. We tend to become this imaginary individual and create toxic behaviors,” he says, critical of the model of the type of man that exists in today’s society. “This project on masculinities is well thought out and it was about time it was thought out, in relation to the theme of the traumas suffered by women,” says Flora, who is convinced that the development of this questioning within the male gender can lead to a positive outcome for everyone. While Bruno points out the potential for disagreement, he nonetheless considers the importance of this topic and the perspectives that can emerge from it. “It can revolutionize all forms of feminism, egalitarianism, racism, ego,” he says, thinking that human conflicts are largely linked to “preconceived ideas about machismo, domination, pride. Hence the importance given to education by the Loba association. “We have been working in a high school in Montreuil for the past three years, where we allow young people in the second year of secondary school to learn about the issue of patriarchy, starting with the question of rape as a weapon of war in the Congo and extending it to the issue of sexual violence against women in the world. And this by showing that the same system of domination exists,” says Bolewa, for whom art is a means of engagement, including political engagement, in the primary sense of the term, namely the life of the city.

Jonathan Baudoin